Black poetry refers to poems written by African Americans in the United States. Yes, some use the term to refer to poetry written by writers from mother nations. In the US alone, there have been many famous black poets including James Mercer, Maya Angelou, Robert Hayden, and many more. All of them helped pave the way for African American poetry.

The Harlem Renaissance in the 20th century saw African Americans making great strides in poetry. Since the movement appeared, black poetry has been on a rise.

Today, we will take a look at American black poets and famous black poets from around the world.

Contents

James Mercer Langston Hughes

Born in February 1901, James was an American poet, but also a social activist and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. He was one of the early innovators of literary art called jazz poetry. Hughes is famous as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance.

James was the one who wrote about the period when “the Negro was in vogue”. It was later paraphrased to “when Harlem was in Vogue”.

Growing up in Midwestern towns, Hughes became a prolific writer at an early age. He moved to New York as a young man and made his career there.

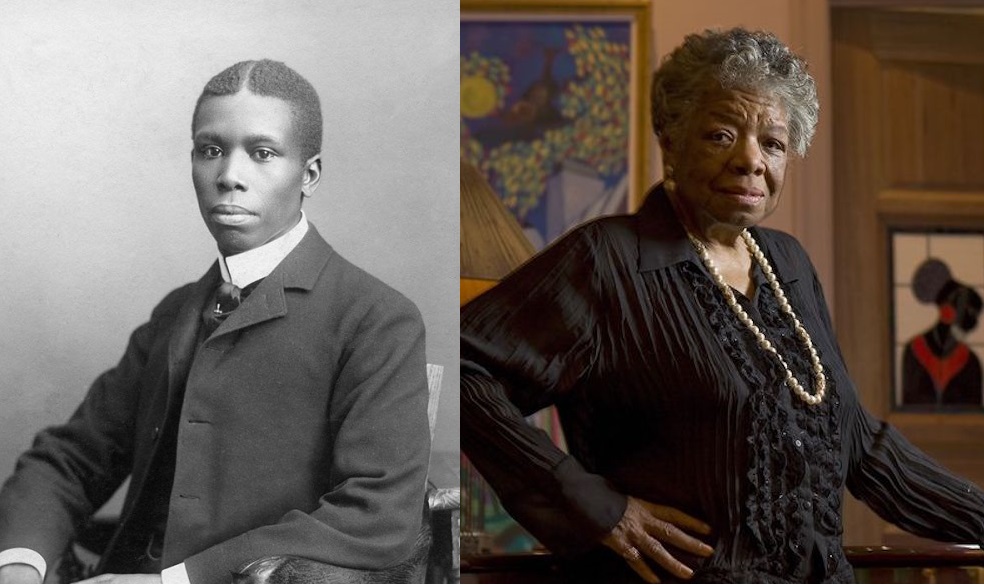

Maya Angelou

Born Marguerite Annie Johnson in April 1928, Maya was an African American poet and civil-rights activist. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, many books of poetry, and more. During her life and poetry career, Maya received a dozen of awards.

She is famous for her series of seven autobiographies focusing on her childhood and early adult experience. The first autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, tells her life story up to age 17 and brought her international acclaim.

Fun fact: Angelou worked many odd jobs during her young adulthood. But after a string of odd jobs, she became a black woman poet and writer. She worked as a fry cook, nightclub performer, sex worker, Porgy and Bess cast member, and many more.

Maya was active during the Civil Rights Movement and worked closely with Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks

Here is another female black poet. Born in June 1917, Gwendolyn was a female American poet and teacher. Her work focused on the personal celebrations and struggles of ordinary people in the community.

Brooks won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1950 for her work Annie Allen. She is the first African American to receive the Pulitzer Prize.

But she received many more awards and honors during her prolific writing career. She was appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1969. She held the position for 32 years until her death.

In 1976, Gwendolyn Brooks became the first black woman inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Robert Hayden

Born in August 1913, Robert was an American essayist, poet, and educator. He was the first African American writer to hold the office as а Consultant in Poetry at the Library of Congress.

He was instrumental in the 1960s during the rise of the Black Arts movement. His work, Ballad of Remembrance was awarded the Grand Prize for Poetry at the first World Festival of Negro Arts in April 1966.

Hayden’s most famous poem is Those Winter Sundays. It deals with the memory of fatherly love and loneliness.

Robert has been praised over the years for his work crafting poems, unique perspectives, exact language, and absolute command of traditional poetic techniques.

Festus Claudius Claude McKay

Born in September 1890, Festus was a Jamaican-American writer and poet. He was also a central figure during the Harlem Renaissance.

McKay was born in Jamaica but traveled to the US to attend college. There, he encountered The Souls of Black Folk, encouraging him to show interest in political involvement.

In 1914, Festus moved to New York City. In 1919, he wrote If We Must Die, one of the best works in black poetry.

Fun fact: following his return to Harlem in 1934, he was in frequent contention with the Stalinist New York City Communist Party which sought to dominate the left politics and the writing community.

Phillis Wheatley Peters

Her name can also be spelled Phyllis and Wheatly. Born in 1753, she was the first African American author of a published book of poetry. She was born in West Africa and then sold into slavery at the age of seven or eight. She was transported to North America, where she was bought by the Wheatley family of Boston.

After she learned to write and read, the family encouraged her to write poetry. She was emancipated by her masters shortly after the publication of her book.

Wheatley married poor grocer John Peters following the death of her masters. She lost three children and died in poverty and obscurity.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Dunbar was born in June 1872. The American novelist and poet began writing stories and verses when he was only a child.

Paul published his first poems at the age of 16 in a Dayton newspaper. His popularity increased after William Dean Howells praised his work.

Dunbar is one of the first African American writers to establish an international reputation. Much of his work was written in the Negro dialect associated with the antebellum South. Yet, he also used the Midwestern regional dialect.

Amiri Baraka

When we talk about famous black poets, we cannot ignore Amiri. Previously known as LeRoi Jones and Imamu Ameer Baraka, he was an American writer and author. Baraka taught at several universities.

His career spanned nearly 52 years. During his career, Amiri’s work ranged from black liberation to white racism.

Derek Walcott

Born in January 1930 on the island of Saint Lucia, Derek initially trained to be a painter. Yet, he soon turned to writing. At the age of 14, he published his first poem in the newspaper The Voice of St. Lucia.

His collection In a Green Night: Poems gave him international acclaim and praise. Yet, his most acclaimed work is The Homeric epic poem Omeros.

Critics cite it as a major achievement. In 1992, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Nobel committee described his work as a “poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment”.

Audre Lorde

Born in New York City to Caribbean immigrants, she attended Hunter College High School. It was a secondary school for intellectually gifted students.

It was there she published her first poem in Seventeen magazine. In 1973, her collection From a Land Where Other People Live was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry.

Lorde had a long and prolific career as a poet. But was also the poet laureate of New York City between 1991 and 1992.

Her poetry is renowned for its technical mastery and emotional expression. Most of her poems are famous for expressing anger and outrage at civil and social injustices.

Audre was a civil rights activist and feminist. She described herself as “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet”.

Nikki Giovanni

Born in 1943 in Knoxville, Tennessee, Nikki is one of the foremost African American poets of America. Her early work was inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement.

Her early work contains a strong, militant African-American perspective. She was often called The Poet of the Black Revolution.

Jupiter Hammon

Let’s finish off the list of African American poets with the man who started everything. He was a black American writer famous as the founder of African American poetry. His poem published in 1761 in New York was the first by an African American in North America.

Hammon published both poetry and prose. He was born into slavery but learned to read and write. In his honor, we celebrate Black Poetry Day on October 17. It is an unofficial holiday celebrated on the anniversary of the birth of Jupiter.