The first famous female poet was Sappho, an ancient Greek poet. She is also one of the earliest known poets in history. Renowned in antiquity and referred to as The Poetess, Sappho paved the way for many famous female poets to follow.

Sappho was viewed in the same way as Homer was viewed. We have had many notable female poets in history, but the 19th century is the most important period. During the 19th century, we saw the emergence of several prominent female poets. They laid the groundwork for the rise of women in the field of poetry.

With that in mind, here are some women poets that we should celebrate to this day.

Contents

Phillis Wheatley

Captured and sold into slavery when she was only seven years old, Phillis is one of the most influential female poets. She was brought to Boston on a slave ship in 1761. There, the Wheatley family bought her as a servant.

They named her Phillis after the ship that brought her to America. So, you can say her original name is lost somewhere. Her new family in the US saw her talent and encouraged her to write.

Wheatley started writing poetry at the age of 13. By the time she was 14, her poems already started being published in newspapers in the United States.

In 1773, she published her first poetry collection. That made Wheatley the first published African American woman.

Her work was praised by prominent US figures, including George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. While she was freed from slavery, Phillis struggled following the death of her masters. She died in poverty at the age of 31.

Christina Georgina Rossetti

Born in December 1830, Christina was an English writer of romantic, devotional, and children’s poems. She wrote two famous Christmas carols that we hear in Britain to this day. Those are In the Bleak Midwinter and Love Came Down at Christmas.

Most of her poems imitated her favored poets. She began experimenting with verse forms, being one of the first women poets to use sonnets, hymns, and ballads. Rossetti drew inspiration and narrative from the Bible and folk tales.

Her most notable collection is Goblin Market and Other Poems. It appeared in 1862 when she was 31 years old. While her popularity did not approach her contemporary peers and faded in the early 20th century, her Christmas carol remains popular to this day. Gustav Holst and Harold Darke made sure of that.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Elizabeth began writing poetry at the early age of six. The poems she wrote at a young age remain some of the largest extant collections of literary work by any young English writer.

Famous for her love sonnet How do I love thee, Elizabeth married renowned English writer Robert Browning. She wrote the love poem during their courtship.

Widely popular in the United Kingdom and the United States during her lifetime, her poetry influenced American writers like Edgar Allan Poe and Emily Dickinson.

Mary Jane Oliver

Born in September 1935, Mary Oliver is a modern female poet on this list. She was an American poet who won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award.

Nature-inspired her work, not the human world. Mary Jane had a lifelong passion for solitary walks in the wild. Her poetry is grounded in memories of Ohio and her adopted home of New England.

She has been compared to Emily Dickinson, with whom she shared an affinity for solitude and inner monologue.

In 2007, the New Times described Mary as “far and away, this country’s best-selling poet”.

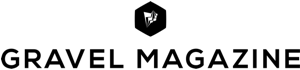

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson

Emily Dickinson is one of the most famous female poets in history. Born in December 1830, she was an American poet. Fun fact: she was little-known during her life.

But following her demise, she has been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Born into a prominent family with strong ties to its community, Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation.

Many considered her an eccentric. Dickinson developed a penchant for white clothing and had a reluctance to greet guests. Later in life, she even refused to leave her bedroom. She never married and most of her friendships depended upon correspondence.

Fun fact: she wrote nearly 1,800 poems. But only 10 were published during her life. The poems she published were edited significantly to fit conventional poetic rules.

Dickinson was ahead of her time. Her poems were unique for her era. Emily’s poems contain short lines, typically lack titles, and often use slant rhyme and unconventional capitalization and punctuation.

Her poems, as well as her letters to friends, deal with themes of death and immortality.

It was not until her death in 1886, that her sister Lavinia Dickinson discovered her cache of poems and published them. Her poems fall into three distinct periods, pre-1861, 1861-1865, and post-1866.

Rupi Kaur

Born in October 1992 in Punjab, India, she immigrated to Canada with her parents when she was only four years old.

Rupi began writing poems for her friends on their birthdays. She was in high school at the moment. At the time, she shared her work anonymously.

Thanks to social media, Kaur began publishing and posting poetry. With time, she became a sensation. Her first poetry collection, Milk and Honey, sold two million copies and was on the New York Times Best Sellers list for 73 weeks.

Rupi is part of the new generation of poets who primarily use social media for their branding. As a famous contemporary poet, her work focuses on love, sex, rejection, and relationships. But she also writes about dark topics like abuse, racism, and beauty standards.

Many consider her a feminist poet and one of the most important in modern feminist poetry.

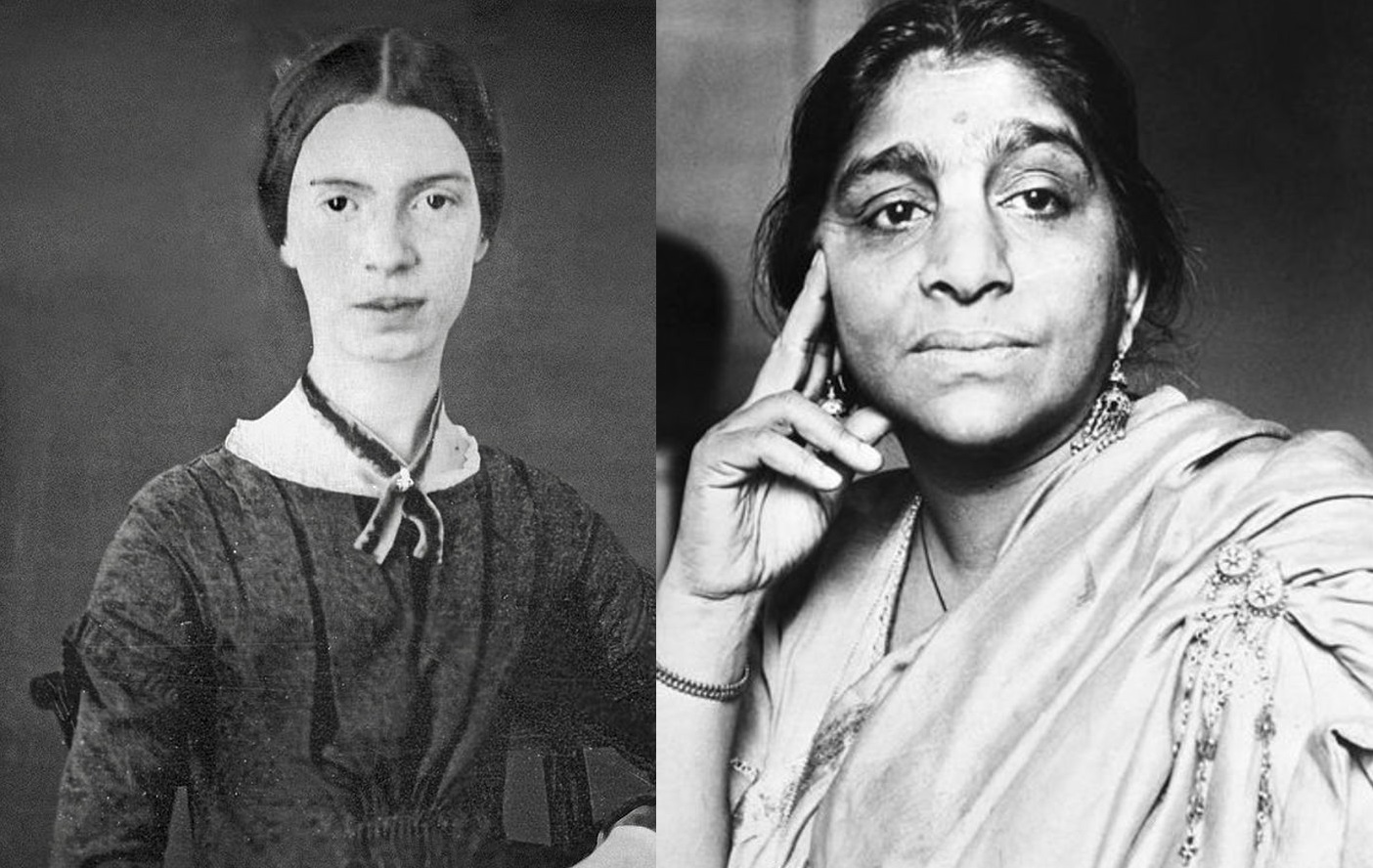

Sarojini Naidu

Born in February 1879, Sarojini was an Indian political activist and Indian poet. She was a proponent of civil rights, women’s emancipation, and anti-imperialistic ideas. You can say she was a feminist poet.

Naidu was an important figure in India’s struggle for independence from colonial rule. Her work earned her the sobriquet “The Nightingale of India” by Mahatma Gandhi.

Her poetry includes children’s poems and serious themes poems. She wrote about romance, tragedy, and patriotism.

Edna St Vincent Millay

Born in February 1892, Edna was an American lyrical poet and playwright. She was encouraged to read classics at home. Vincent Millay started winning poetry prizes and poetry awards early on. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 1923.

As a prominent social figure in New York City’s Greenwich Village, she was praised for her uninhibited lifestyle. Edna formed many relationships with both men and women.

Her legacy is the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in poetry. She wrote six verse dramas early in her career.

Sylvia Plath

We cannot have a list of notable female American poets and famous female writers without Sylvia Plath. Born in October 1932, she was an American poet, novelist, and short-story writer. Plath is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry.

Famous for her collections Ariel, The Bell Jar, and The Colossus and Other Poems, Sylvia won the Pulitzer Prize in poetry in 1982. She is the fourth person to receive the honor posthumously.

Her most important work remains The Bell Jar, which is a semi-autobiographical novel published shortly before her death in 1963.

Clinically depressed for most of her life, she was treated with electroconvulsive therapy, ECT, multiple times. In 1963, she committed suicide.

Her poems exhibit what became her typical imagery, using personal and nature-based depictions. Her poems feature the moon, blood, hospitals, fetuses, and skulls.

Her landscape poetry has been described as a rich and important area of her work. Some of her best landscape poetry is about the Yorkshire moors.

Maya Angelou

Maya is a famous female poet and a famous black poet. She was instrumental in the Civil Rights movement. Born Marguerite Annie Johnson, Maya was one of the most renowned figures of the 20th century.

She worked odd jobs before starting to write. Angelou worked as a singer and dancer and then writing moved her forward in life toward civil rights and journalism.

In her poems, Angelou explored themes like women, loss, music, struggle, discrimination, racism, and more. Referred to as people’s poet and the black woman’s poet laureate, Maya wrote mostly about African Americans. That is why her poems remain popular and have been called the anthems of African Americans.