Before the Spanish conquest in the 16th century, Mexico came under a region called Mesoamerica. The art in Mesoamerica had a lot of natural elements. Other elements in Mesoamerican art included political reality and the gods. Following the Spanish conquests, famous Mexican paintings used art to propagate Christianity.

And after Mexico won its independence in 1821, the art shifted again. This time, art celebrated the heroes of independence. Indigenous themes started appearing in paintings and sculptures.

The Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1920 also had a huge impact on art. It radically transformed Mexican culture, starting the muralism movement. Murals depicted nationalistic, social, and political messages.

Mexico is one of the most unique cultures in the Western hemisphere. Taking a closer look at the famous Mexican paintings reveals a lively and warm culture and concepts from the entire Mexican history.

Contents

The Two Frida’s

Frida Kahlo is one of the most famous Mexican artists. Famous worldwide, the legendary Frida painted a lot of gripping and bizarre self-portraits. Historians consider The Two Fridas a defining piece in Mexican art culture.

Famous for living passionately in real life, her artwork reflects her lifestyle. This painting serves as a vivid depiction of her duality. Many historians tie the duality with her divorce with another famous Mexican painter, Diego Rivera.

She completed the painting in 1939. It shows one version of the artist dressed in a beautiful and flowing white dress. It is the same as the fashion of European women at the time.

The second Frida, however, wears a traditional Mexican-style dress. And that one fits the Mexican appearance of the artist more.

The left Frida, or the European one, features a bleeding heart torn. And the one on the right, the Mexican Frida, has her heart unscathed.

The duality shows her dilemma. She knew she belongs to the Mexican culture. Yet, she had a strong desire to assimilate with the more popular European style.

Because of the work highlighting her belief in her Mexican roots, art critics consider it the most moving Mexican painting in existence.

The History of Mexico

Here is a famous painting by Frida’s former husband and partner, Diego Rivera. They are the two best and most famous Mexican artists.

Diego made this Mexican folk art painting as a mural upon a large main staircase inside the National Palace of Mexico City. His work often featured scenes from a historical context. He began working on the mural in 1929 and completed it six years later.

The painting depicts the history from the native Aztec period, up until present-day Mexico. The scenes on the mural defined the country to its core.

One scene shows the indigenous people getting overtaken by Christian influence and centuries that followed under the Catholic faith.

For this painting, Rivera put a huge focus on the nation’s struggle for independence from Spain. You can notice a lot of famous figures that shaped Mexico throughout its history.

Echo of a Scream

David Alfaro Siqueiros painted Echo of a Scream. He, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco are the “Three Greats of Mexican muralists”. Or as they call them in Mexico, “los tres grandes”. David is the most radical among the three. In his paintings and murals, he depicts the human struggle against an authoritarian regime.

Echo of a Scream is his most famous work. It depicts the bleakness, despair, and destruction of war. He painted it during the Spanish Civil War. The captivating work visually and metaphorically captures human suffering during the war.

The enlarged head of a crying baby serves as the most prominent figure in the painting. There is another baby coming out of his mouth.

Self-Portrait: The Inn of the Dawn Horse

Leonora Carrington is another Mexican artist that loved doing self-portraits. But she and Frida Kahlo work in a different way.

Many historians and art critics consider Leonora the most famous female Surrealist artist. And unlike other Surrealists, she did not show interest in the writings of Sigmund Freud. Instead, she got famous for her haunting and autobiographical paintings. They incorporate images of sorcery, metamorphosis, alchemy, and the occult.

The Inn of the Dawn Horse is her most acclaimed work. In the self-portrait, she painted herself posed in the foreground on a blue armchair. Her hand points toward a female hyena. You can also notice a white rocking horse floating on the wall behind her head. And there is a white horse galloping freely in the background.

Critics consider the distorted perspective and mysterious narrative as her attempt to reimagine her own reality.

Broken Column

We have another painting by Frida Kahlo. The Broken Column is an amazing self portrait evoking more than just superficial beauty.

In the summer of 1925, she got involved in a serious bus accident. Because of it, she continued living with severe pain and nagging injuries. Frida underwent more than 30 surgeries trying to repair the damage done to her. And because of the accident, she could never bear children. This one weighed heavily on her mind.

The famous Mexican artist completed The Broken Column in 1944, many years after the accident. But she used the accident as an inspiration. The painting portrays a semi-nude Kahlo in a beautiful white dress. The nails on her body symbolize the persistent pain. She also paints her broken spine, representing the damage she has to endure to continue with her life.

The barren landscape in the background points to the fact she couldn’t have children because of the accident.

La Calavera Catrina

Jose Guadalupe Posada did this iconic piece in 1913. It features a simple, yet elegantly-dressed female skeleton posing in a smiling fashion. The skeleton wears a lavish hat. The bizarre paradox pays homage to the European and foreign influence in the nation.

He wanted to highlight the relationship between Mexico and Europe in a satirical way. We can say for sure he caught the attention of viewers. And because of that, they had to consider the meaning behind the painting.

La Calavera Catrina is an iconic figure of the Mexican Day of the Dead.

Detroit Industry Murals

This is another mural by Diego Rivera. He did this in 1933. Many consider Rivera a genius who could turn to any style, including Mexican muralism. Some classify him as Cubist, Flemish, Impressionist, or Post-Impressionist. But Diego could do anything he wanted.

In 1932, he got commissioned to paint 27 frescoes in the Detroit Institute of Art in Midtown Detroit. The two largest found their place on the north and south walls. These two murals depict laborers working at Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge Plant.

Other panels depict advances in scientific fields, including technology and medicine. Rivera himself considers the mural his most successful work.

In 2014, these murals got National Historic Landmark Status.

Man at the Crossroads

While Diego Rivera considers the Detroit murals his most successful work, critics point to Man at the Crossroads.

The Rockefellers commissioned the famous Mexican artist this fresco for the ground floor wall of the Rockefeller Center in New York City. However, he didn’t complete it. Diego refused to remove a portrait of Lenin, causing controversy in the process.

Thanks to his black and white photographs, he recreated a nearly identical mural at the Palacio de Bellas Artest in Mexico City.

The second mural got the name Man, Controller of the Universe. The composition depicts a contrast between Capitalism and Socialism. Wealthy people play cards and smoke on the left. And on the right, Lenin holds hands with a multi-racial group of workers.

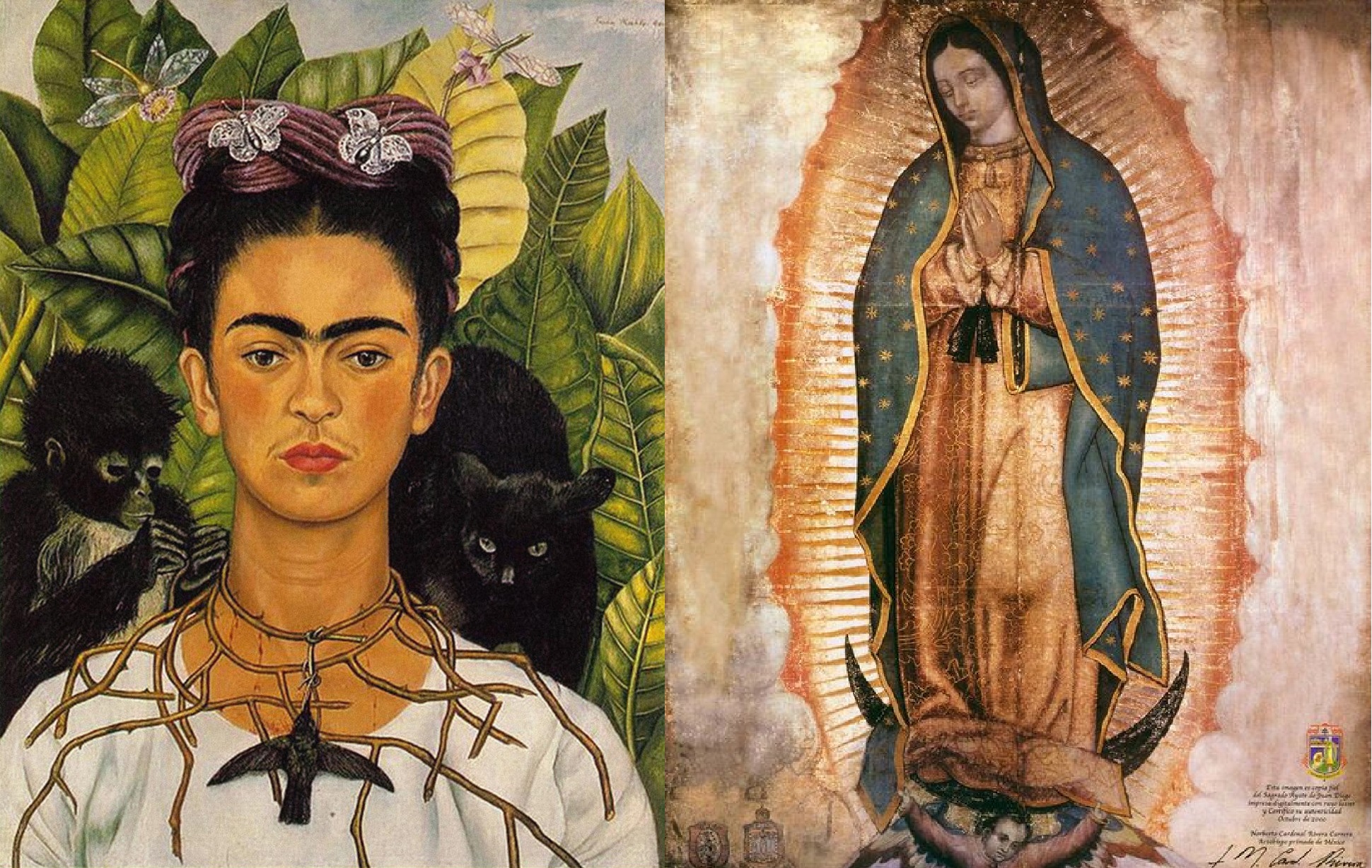

Our Lady of Guadalupe

According to a legend, Blessed Virgin Mary appeared in Mexico before a 57-year old peasant by the name of Juan Diego. He was an Aztec, and converted to Christianity. Mary requested the peasant to build her a shrine on the spot. But the archbishop asked for proof. Juan Diego returned to Mary and told her.

Mary instructed the peasant to climb at the top of the hill and gather flowers. There, he found Castilian roses, which were neither in season nor native to the region. Mary had arranged the flowers in a burlap-type cloak. She told him to open the cloak only upon his return to the bishop.

When the peasant did so, the flowers fell to the floor and left on the surface of his cloak the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The image got enshrined within the Minor Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City.

Some people believe this to be the most famous Mexican folk art painting of all-time.

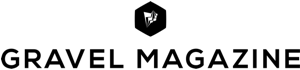

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird

We finish the list of famous Mexican paintings with another self-portrait by Frida Kahlo. She did this one in 1940.

In her self-portraits, she uses symbolism to portray her physical and psychological wounds. In this portrait, she wears a thorn necklace. You can see blood trickling from the wounds made by the thorns. On the left and right side, you can see a black monkey and a black cat. Hummingbird hangs freely from the thorn necklace.

Kahlo identified herself with the indigenous Mexican culture. She used this portrait to show it. The black panther is a symbol of bad luck and death, the monkey symbolizes evil, and the hummingbird’s freedom and love.

Art critics believe this self-portrait places her amid symbols of colonial and male repression.