Chicago architecture and Chicago buildings have a far greater impact than only the Midwestern United States. Chicago architectural style has influenced the history of American architecture. Over the years, famous Chicago architects have changed the landscape of the third most populous city in the US. The city’s history is tangled around the architecture.

The city is world-famous for its plethora of unique architectural style. But most importantly, the skyscrapers.

In the early 1880s, architectural pioneers explored steel-frame construction, and in the 1890s, the use of large areas of plate glass. Architects in Chicago built some of the first modern skyscrapers. For example, William LeBaron Jenney’s Home Insurance Building was completed in 1885. To this day, it is considered the first building to use steel in its structural frame instead of cast iron.

Among the plethora of famous Chicago architects, Louis Sullivan was the most popular and most philosophical. He realized that skyscrapers are basically a new form of architecture. So, he discarded historical precedent and designed buildings that put emphasis on vertical nature.

Sullivan was the one to pioneer the new style, famous as a Commercial style. Later on, it was called Chicago School by historians.

Fun fact: at one point, Chicago had the tallest skyscraper in the US, not New York. The Masonic Temple got that title in 1892 and held it for two years before another New York City building took it over. So do not underestimate the Chicago skyline.

Contents

Chicago Architecture Style

What is the Chicago architecture style? Referred to as Chicago School, much of the early work is known as the Commercial style. The first school was a school of architects in the late 19th century. Then, it continued to the turn of the 20th century.

Architects of Chicago were the first to promote new technologies like steel-frame construction in commercial buildings. They developed a spatial aesthetic that evolved and influenced parallel developments in European modernism.

The Second Chicago School emerged in the 1940s with a modernist aesthetic. This one pioneered technologies and structural systems, for example, tube-frame structure.

To this day, some of the distinguished features of Chicago architecture include steel-frame buildings with masonry cladding, and allowing large plate-glass window areas. You can also notice elements of neoclassical architecture for the skyscrapers.

What separates Chicago skyscraper buildings from other skyscrapers is they contain three parts of a classical column. The lowest functions as the base, the middle stories, and the last floor or two are capped with a cornice. Often, the last one has ornamental details that represent the capital.

Another feature is the Chicago window. It is a three-part window consisting of a large fixed center panel flanked by two smaller double-hung sash windows.

Most Famous Chicago Architects

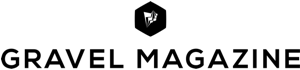

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Ludwig designed the Crown Hall in 1956. He is referred to as Mies by architecture enthusiasts. He shaped the mid-century modernism style by his lifelong work.

He became famous with his futuristic and open-spaced buildings, but in Europe, not in the US. For example, he designed the open-spaced Barcelona Pavilion in 1929.

When he arrived in Chicago, he became the head of the architecture department at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

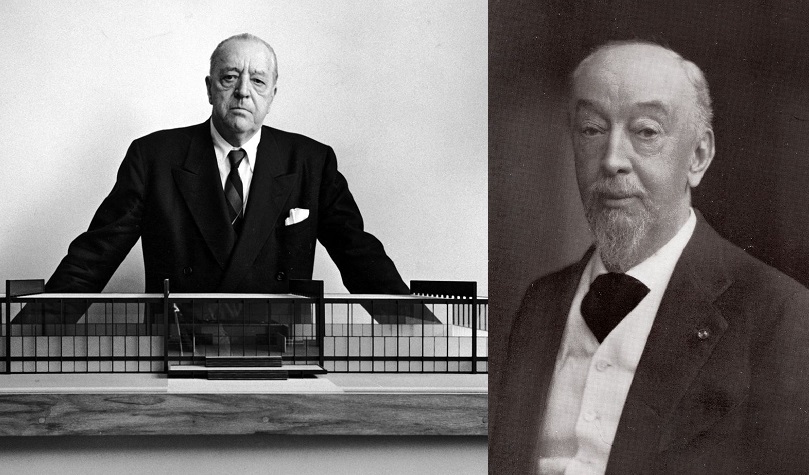

Louis Sullivan

Arguably the greatest Chicago architect. When you speak of really tall buildings, you cannot ignore his name. Many call him the Father of skyscrapers. He was a mentor of Frank Lloyd Wright and a founding member of the Prairie School.

He built a legacy through his work, namely the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store in 1899. Sullivan is responsible for defining the aesthetic of early skyscrapers and elevating the visual appeal of such buildings to new heights.

Louis used terracotta, wood, and iron to create unique and intricate designs adorning the exterior surface of the buildings.

Many young designers and young architects quote his famous mantra, “form follows function”.

Daniel Burnham

He designed the Union Station Great Hall, built in 1925. Daniel was a champion of revolutionary achievement. Famous for designing the Reliance Building, it was the first skyscraper to feature large plate-glass windows.

His Union Station building is considered the Beaux-arts masterpiece. Fun fact: he tried a career in politics, but was unsuccessful. Following his unsuccessful career in politics, he turned his pen to paper and drafted buildings like the Masonic temple building.

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank is a Chicago native architect. Considered by many the godfather of mid-century modernism and the Prairie style homes, he made a name for himself with the Moore-Dugal Residence, the Robie House, Taliesin studio in Spring Green, and many more.

People started noticing his Prairie-style homes and modern designs. He is arguably the most renowned American architect. Determined to define American architecture, he worked in Sullivan’s firm for the early part of his architecture career. Following his departure, he continued to develop his residential design.

Why were his houses called prairie houses? Because of the way they complemented the Chicago landscape. They feature shallow, sloping roofs, clean lines, and suppressed chimneys. Historians consider them among the early examples of open-plan layouts.

Wright revolutionized the architecture of the 20th century. If you want to see his work, just take a short trip in Chicago to the suburbs and observe his home, as well as the Frank Lloyd Wright Historic District.

Edward J. Burling

He was among the early settlers and a favorite architect of many. Burling inspired many with his timeless design, dedication to the community, and willingness to begin anew following the Chicago fire of 1871.

His work stands at the Nickerson Mansion or the Driehaus museum, the DeKoven House, and St. Jones Cathedral.

William Le Baron Jenney

He created the world’s first skyscraper. As a famous architect, he was also a pioneer in using metal-frame buildings in his work for the New York Home Insurance Company. He used fire-resistant material and stone columns that helped make the structure fireproof.

The company asked for a fireproof building because fires were a big thing back then. And he delivered.

Notable Buildings in Chicago

Now that we talked about the famous Chicago architects that shaped Chicago architecture, let’s take a look at some of the notable buildings in the capital of Illinois.

– Leiter I Building

– Montauk Building

– Rookery Building

– Auditorium Building

– Leiter II Building

– Monadnock Building

– Marquette Building

– Reliance Building

– Fisher Building

– Sullivan Center

– Brooks Building

– Cage Group Buildings